In this blog, I’ll look at CVE-2022-46395, a variant of Project Zero issue 2327 (CVE-2022-36449) and show how it can be used to gain arbitrary kernel code execution and root privileges from the untrusted app domain on an Android phone that uses the Arm Mali GPU. I used a Pixel 6 device for testing and reported the vulnerability to Arm on November 17, 2022. It was fixed in the Arm Mali driver version r42p0, which was released publicly on January 27, 2023, and fixed in Android in the May security update. I’ll go through imported memory in the Arm Mali driver, the root cause of Project Zero issue 2327, as well as exploiting a very tight race condition in CVE-2022-46395. A detailed timeline of this issue can be found here.

In this blog, I’ll look at CVE-2022-46395, a variant of Project Zero issue 2327 (CVE-2022-36449) and show how it can be used to gain arbitrary kernel code execution and root privileges from the untrusted app domain on an Android phone that uses the Arm Mali GPU. I used a Pixel 6 device for testing and reported the vulnerability to Arm on November 17, 2022. It was fixed in the Arm Mali driver version r42p0, which was released publicly on January 27, 2023, and fixed in Android in the May security update. I’ll go through imported memory in the Arm Mali driver, the root cause of Project Zero issue 2327, as well as exploiting a very tight race condition in CVE-2022-46395. A detailed timeline of this issue can be found here.

Imported memory in the Arm Mali driver

The Arm Mali GPU can be integrated in various devices (for example, see “Implementations” in Mali (GPU) Wikipedia entry). It has been an attractive target on Android phones and has been targeted by in-the-wild exploits multiple times.

In September 2022, Jann Horn of Google’s Project Zero disclosed a number of vulnerabilities in the Arm Mali GPU driver that were collectively assigned CVE-2022-36449. One of the issues, 2327, is particularly relevant to this research.

When using the Mali GPU driver, a user app first needs to create and initialize a kernel object. This involves the user app opening the driver file and using the resulting file descriptor to make a series of calls. A object is responsible for managing resources for each driver file that is opened and is unique for each file handle.kbase_contextioctlkbase_context

In particular, the manages different types of memory that are shared between the GPU devices and user space applications. The Mali driver provides the that allows users to share memory with the GPU via direct I/O (see, for example, the “Performing Direct I/O” section here). In this setup, the shared memory is owned and managed by the user space application. While the kernel driver is using the memory, the function is used to increase the refcount of the user page so that it does not get freed while the kernel is using it.kbase_contextKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_IMPORTioctlget_user_pages

Memory imported from user space using direct I/O are represented by a with the .kbase_va_regionKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_memory_type

A in the Mali GPU driver represents a shared memory region between the GPU device and the host device (CPU). It contains information such as the range of the GPU addresses and the size of the region. It also contains two pointer fields, and , that are responsible for keeping track of the memory pages that are mapped to the GPU. In our setting, these two fields point to the same object, so I’ll only refer to them as the from now on, and code snippets that use should be understood to be applied to the as well. In order to keep track of the pages that are currently being used by the GPU, the contains an array, , that keeps track of these pages.kbase_va_regionkbase_mem_phy_alloccpu_allocgpu_allocgpu_alloccpu_allocgpu_allockbase_mem_phy_allocpages

For type of memory, the array in is populated by using the function on the pages that are supplied by the user. This function increases the refcount of those pages, and then adds them to the array while they are in use by the GPU, and then removes them from and decreases their refcount once the GPU is no longer using the pages. This ensures that the pages won’t be freed while the GPU is using them.KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFpagesgpu_allocget_user_pagespagespages

Depending on whether the user passes the flag when the memory is imported via the , the user pages are either added to when the memory region is imported (when is set), or it is only added to when the memory is used at a later stage.KBASE_REG_SHARED_BOTHKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_IMPORTioctlpagesKBASE_REG_SHARED_BOTHpages

In the case where are populated when the memory is imported, the pages cannot be removed until the and its is freed. When is not set and the are populated “on demand,” the memory management becomes more interesting.pageskbase_va_regiongpu_allocKBASE_REG_SHARED_BOTHpages

Project zero issue 2327 (CVE-2022-36449)

When the of a are not populated at import time, the memory can be used by submitting a GPU software job (“softjob”) that uses the imported memory as an external resource. I can submit a GPU job via the with the requirement, and specify the GPU address of the shared user memory as its external resource:pagesKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFKBASE_IOCTL_JOB_SUBMITioctlBASE_JD_REQ_EXTERNAL_RESOURCES

struct base_external_resource extres = {

.ext_resource = user_buf_addr; //<------ GPU address of the imported user buffer

};

struct base_jd_atom atom1 = {

.atom_number = 0,

.core_req = BASE_JD_REQ_EXTERNAL_RESOURCES,

.nr_extres = 1,

.extres_list = (uint64_t)&extres,

...

};

struct kbase_ioctl_job_submit js1 = {

.addr = (uint64_t)&atom1,

.nr_atoms = 1,

.stride = sizeof(atom1)

};

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_JOB_SUBMIT, &js1);

When a software job requires external memory resources that are mapped as , the function is called to insert the user pages into the array of the of the via the call:KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_jd_user_buf_mappagesgpu_allockbase_va_regionkbase_jd_user_buf_pin_pages

static int kbase_jd_user_buf_map(struct kbase_context *kctx,

struct kbase_va_region *reg)

{

...

int err = kbase_jd_user_buf_pin_pages(kctx, reg); //<------ inserts user pages

...

}

At this point, the user pages have their refcount incremented by and the physical addresses of their underlying memory are inserted into the array.get_user_pagespages

Once the software job finishes using the external resources, is used for removing the user pages from the array and then decrementing their refcounts.kbase_jd_user_buf_unmappages

The array, however, is not the only way that these memory pages may be accessed. The kernel driver may also create memory mappings for these pages that allow them to be accessed from the GPU and the CPU, and these memory mappings should be removed before the pages are removed from the array. For example, , the caller of , takes care to remove the memory mappings in the GPU by calling :pagespageskbase_unmap_external_resourcekbase_jd_user_buf_unmapkbase_mmu_teardown_pages

void kbase_unmap_external_resource(struct kbase_context *kctx,

struct kbase_va_region *reg, struct kbase_mem_phy_alloc *alloc)

{

...

case KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUF: {

alloc->imported.user_buf.current_mapping_usage_count--;

if (alloc->imported.user_buf.current_mapping_usage_count == 0) {

bool writeable = true;

if (!kbase_is_region_invalid_or_free(reg) &&

reg->gpu_alloc == alloc)

kbase_mmu_teardown_pages( //kbdev,

&kctx->mmu,

reg->start_pfn,

kbase_reg_current_backed_size(reg),

kctx->as_nr);

if (reg && ((reg->flags & (KBASE_REG_CPU_WR | KBASE_REG_GPU_WR)) == 0))

writeable = false;

kbase_jd_user_buf_unmap(kctx, alloc, writeable);

}

}

...

}

It is also possible to create mappings from these userspace pages to the CPU by calling on the Mali drivers file with an appropriate page offset. When the userspace pages are removed, these CPU mappings should be removed by calling the function to prevent them from being accessed from the user space addresses. This, however, was not done when user pages were removed from the memory region, meaning that, once the refcounts of these user pages were reduced in , these pages could be freed while CPU mappings to these pages created by the Mali driver still had access to them. This, in particular, meant that after these pages were freed, they could still be accessed from the user application, creating a use-after-free condition for memory pages that was easy to exploit.mmapkbase_mem_shrink_cpu_mappingmmap'edKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_jd_user_buf_unmap

Root cause analysis can sometimes be more of an art than a science and there can be many valid, but different views of what causes a bug. While at one level, it may look like it is simply a case where some cleanup logic is missing when the imported user memory is removed, the bug also highlighted an interesting deviation in how imported memory is managed in the Mali GPU driver.

In general, shared memory in the Mali GPU driver is managed via the of the and there are two different cases where the backing pages of a region can be freed. First, if the and the themselves are freed, then the backing pages of the are also going to be freed. To prevent this from happening, when the backing pages are used by the kernel, references of the corresponding and are usually taken to prevent them from being freed. When a CPU mapping is created via , a structure is created and stored as the of the created virtual memory (vm) area. The stores and increases the refcount of both the and , preventing them from being freed while the vm area is in use.gpu_allockbase_va_regiongpu_allockbase_va_regionkbase_va_regiongpu_allockbase_va_regionkbase_cpu_mmapkbase_cpu_mappingvm_private_datakbase_cpu_mappingkbase_va_regiongpu_alloc

static int kbase_cpu_mmap(struct kbase_context *kctx,

struct kbase_va_region *reg,

struct vm_area_struct *vma,

void *kaddr,

size_t nr_pages,

unsigned long aligned_offset,

int free_on_close)

{

struct kbase_cpu_mapping *map;

int err = 0;

map = kzalloc(sizeof(*map), GFP_KERNEL);

...

vma->vm_private_data = map;

...

map->region = kbase_va_region_alloc_get(kctx, reg);

...

map->alloc = kbase_mem_phy_alloc_get(reg->cpu_alloc);

...

}

When the memory region is of type , its backing pages are owned and maintained by memory region, the backing pages can also be freed by shrinking the backing store. For example, using the , would call to remove the backing pages:KBASE_MEM_TYPE_NATIVEKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_COMMITioctlkbase_mem_shrink

int kbase_mem_shrink(struct kbase_context *const kctx,

struct kbase_va_region *const reg, u64 new_pages)

{

...

err = kbase_mem_shrink_gpu_mapping(kctx, reg,

new_pages, old_pages);

if (err >= 0) {

/* Update all CPU mapping(s) */

kbase_mem_shrink_cpu_mapping(kctx, reg,

new_pages, old_pages);

kbase_free_phy_pages_helper(reg->cpu_alloc, delta);

...

}

...

}

In the above, both and are called to remove potential uses of the backing pages before they are freed. As frees the backing pages by calling , it only makes sense to shrink a region where the backing store is owned by the GPU. Even in this case, care must be taken to remove potential references to the backing pages before freeing them. For other types of memory, references to the backing pages may exist outside of the memory region, resizing it is generally forbidden and the array is immutable throughout the lifetime of the . In this case, the backing pages should live as long as the .kbase_mem_shrink_gpu_mappingkbase_mem_shrink_cpu_mappingkbase_mem_shrinkkbase_free_phy_pages_helperpagesgpu_allocgpu_alloc

This makes the semantics of region interesting. While it’s backing pages are owned by the user space application that creates it, as we have seen, its backing store, which is stored in the array of its , can indeed change and backing pages can be freed while the is still alive. Recall that if is not set when the region is created, its backing store will only be set when it is used as an external resource in a GPU job, in which is called to insert user pages to its backing store:KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFpagesgpu_allocgpu_allocKBASE_REG_SHARED_BOTHkbase_jd_user_buf_pin_pages

static int kbase_jd_user_buf_map(struct kbase_context *kctx,

struct kbase_va_region *reg)

{

...

int err = kbase_jd_user_buf_pin_pages(kctx, reg); //<------ inserts user pages

...

}

The backing store then shrinks back to zero after the job has finished using the memory region by calling . This, as we have seen, can result in cleanup logic from being omitted by mistake due to the need to reimplement complex memory management logic. However, this also means the backing store of a region can be removed without going through or freeing the region, which is unusual and may break the assumptions made in other parts of the code.kbase_jd_user_buf_unmapkbase_mem_shrinkkbase_mem_shrink

CVE-2022-46395

The idea is to look for code that accesses the backing store of a memory region and see if it implicitly assumes that the backing store is only removed when either of the followings happens:

- When the memory region is freed, or

- When the backing store is shrunk by the call

kbase_mem_shrink

It turns out that the function had made these assumptions. The function is used by the driver to temporarily map the backing pages of a memory region to the kernel address space via so that it can access them. It calls to perform the mapping. To prevent the region from being freed while the is valid, a is created for the lifetime of the mapping, which also holds a reference to the of the :kbase_vmap_protkbase_vmap_protvmapkbase_vmap_phy_pagesvmapkbase_vmap_structgpu_allockbase_va_region

static int kbase_vmap_phy_pages(struct kbase_context *kctx,

struct kbase_va_region *reg, u64 offset_bytes, size_t size,

struct kbase_vmap_struct *map)

{

...

map->cpu_alloc = reg->cpu_alloc;

...

map->gpu_alloc = reg->gpu_alloc;

...

kbase_mem_phy_alloc_kernel_mapped(reg->cpu_alloc);

return 0;

}

The refcounts of and are incremented in before entering this function. To prevent the backing store from being shrunk by , also calls , which increments in the :map->cpu_allocmap->gpu_allockbase_vmap_protkbase_mem_commitkbase_vmap_phy_pageskbase_mem_phy_alloc_kernel_mappedkernel_mappingsgpu_alloc

static inline void

kbase_mem_phy_alloc_kernel_mapped(struct kbase_mem_phy_alloc *alloc)

{

atomic_inc(&alloc->kernel_mappings);

}

This prevents from shrinking the backing store of the memory region while it is mapped by , as will check the of a memory region:kbase_mem_commitkbase_vmap_protkbase_mem_commitkernel_mappings

int kbase_mem_commit(struct kbase_context *kctx, u64 gpu_addr, u64 new_pages)

{

...

if (atomic_read(®->cpu_alloc->kernel_mappings) > 0)

goto out_unlock;

...

}

When is used outside of , it is always used within the of the corresponding . As mappings created by are only valid with this lock held, other uses of cannot free the backing pages while the mappings are in use either.kbase_mem_shrinkkbase_mem_commitjctx.lockkbase_contextkbase_vmap_protkbase_mem_shrink

However, as we have seen, a memory region can remove its backing store without going through . In fact, the can be used to trigger to remove its backing pages without holding the of the . This means that many uses of are vulnerable to a race condition that can remove its page while the mapping is in use, causing a use-after-free in the memory pages. For example, the calls the , which uses to create a mapping, and then unmap it after the kernel finishes writing to it:KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_mem_shrinkKBASE_IOCTL_STICKY_RESOURCE_UNMAPkbase_unmap_external_resourcejctx.lockkbase_contextkbase_vmap_protvmap'edKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEioctlkbase_write_soft_event_statuskbase_vmap_prot

static int kbasep_write_soft_event_status(

struct kbase_context *kctx, u64 evt, unsigned char new_status)

{

...

mapped_evt = kbase_vmap_prot(kctx, evt, sizeof(*mapped_evt),

KBASE_REG_CPU_WR, &map);

//Race window start

if (!mapped_evt)

return -EFAULT;

*mapped_evt = new_status;

//Race window end

kbase_vunmap(kctx, &map);

return 0;

}

If the memory region that belongs to is of type , then between and , the memory region can have its backing pages removed by another thread using the . There are other uses of in the driver, but they follow a similar usage pattern and the use in has a simpler call graph, so I’ll stick to it in this research.evtKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_vmap_protkbase_vunmapKBASE_IOCTL_STICKY_RESOURCE_UNMAPioctlkbase_vmap_protKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATE

The problem? The race window is very, very tiny.

Winning a tight race and widening the race window

The race window in this case is very tight and consists of very few instructions, so even hitting it is hard enough, let alone trying to free and replace the backing pages inside this tiny window. In the past, I’ve used a technique from Exploiting race conditions on [ancient] Linux of Jann Horn to widen the race window. While the technique can certainly be used to widen the race window here, it lacks the fine control in timing that I need here to hit the small race window. Fortunately, another technique that was also developed by Jann Horn in Racing against the clock—hitting a tiny kernel race window is just what I need here.

The main idea of controlling race windows on the Linux kernel using these techniques is to interrupt a task inside the race window, causing it to pause. By controlling the timing of interrupts and the length of these pauses, the race window can be widened to allow other tasks to run within it. In the Linux kernel, there are different ways in which a task can be interrupted.

The technique in Exploiting race conditions on [ancient] Linux uses task priorities to manipulate interrupts. The idea is to pin a low priority task on a CPU, and then run another task with high priority on the same CPU during the race window. The Linux kernel scheduler will then interrupt the low priority task to allow the high priority task to run. While this can stop the low priority task for a long time, depending on how long it takes the high priority task to run, it is difficult to control the precise timing of the interrupt.

The Linux kernel also provides APIs that allow users to schedule an interrupt at a precise time in the future. This allows more fine-grain control in the timing of the interrupts and was explored in Racing against the clock—hitting a tiny kernel race window. One such API is the . A is a file descriptor where its availability can be scheduled using the hardware timer. By using the syscall, I can create a , and schedule it to be ready for use in a future time. If I have epoll instances that monitor the , then by the time the is ready, the epoll instances will be iterated through and be woken up.timerfdtimerfdtimerfd_settimetimerfdtimerfdtimerfd

migrate_to_cpu(0); //<------- pin this task to a cpu

int tfd = timerfd_create(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, 0); //<----- creates timerfd

//Adds epoll watchers

int epfds[NR_EPFDS];

for (int i=0; i<NR_EPFDS; i++)

epfds[i] = epoll_create1(0);

for (int i=0; i<NR_EPFDS; i++) {

struct epoll_event ev = { .events = EPOLLIN };

epoll_ctl(epfd[i], EPOLL_CTL_ADD, fd, &ev);

}

timerfd_settime(tfd, TFD_TIMER_ABSTIME, ...); //<----- schedule tfd to be available at a later time

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATE,...); //<---- tfd becomes available and interrupts this ioctl

In the above, I created a , , using , and then added epoll watchers to it using the syscall. After this, I schedule to be available at a precise time in the future, and then run the . If the becomes available while the is running, then it’ll be interrupted and the epoll watchers of are processed instead. By creating a large list of epoll watchers and scheduling so that it becomes available inside the race window of , I can widen the race window enough to free and replace the backing stores of my memory region. Having said that, the race window is still very difficult to hit and most attempts to trigger the bug will fail. This means that I need some ways to tell whether the bug has triggered before I continue with the next step of the exploit. Recall that the race window happens between the calls and :timerfdtfdtimerfd_createepoll_ctltfdKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEioctltfdKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEtfdtfdKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_vmap_protkbase_vunmap

static int kbasep_write_soft_event_status(

struct kbase_context *kctx, u64 evt, unsigned char new_status)

{

...

mapped_evt = kbase_vmap_prot(kctx, evt, sizeof(*mapped_evt),

KBASE_REG_CPU_WR, &map);

//Race window start

if (!mapped_evt)

return -EFAULT;

*mapped_evt = new_status;

//Race window end

kbase_vunmap(kctx, &map);

return 0;

}

The call holds the for almost the entire duration of the function:kbase_vmap_protkctx->reg_lock

void *kbase_vmap_prot(struct kbase_context *kctx, u64 gpu_addr, size_t size,

unsigned long prot_request, struct kbase_vmap_struct *map)

{

struct kbase_va_region *reg;

void *addr = NULL;

u64 offset_bytes;

struct kbase_mem_phy_alloc *cpu_alloc;

struct kbase_mem_phy_alloc *gpu_alloc;

int err;

kbase_gpu_vm_lock(kctx); //reg_lock

...

out_unlock:

kbase_gpu_vm_unlock(kctx); //reg_lock

return addr;

fail_vmap_phy_pages:

kbase_gpu_vm_unlock(kctx);

kbase_mem_phy_alloc_put(cpu_alloc);

kbase_mem_phy_alloc_put(gpu_alloc);

return NULL;

}

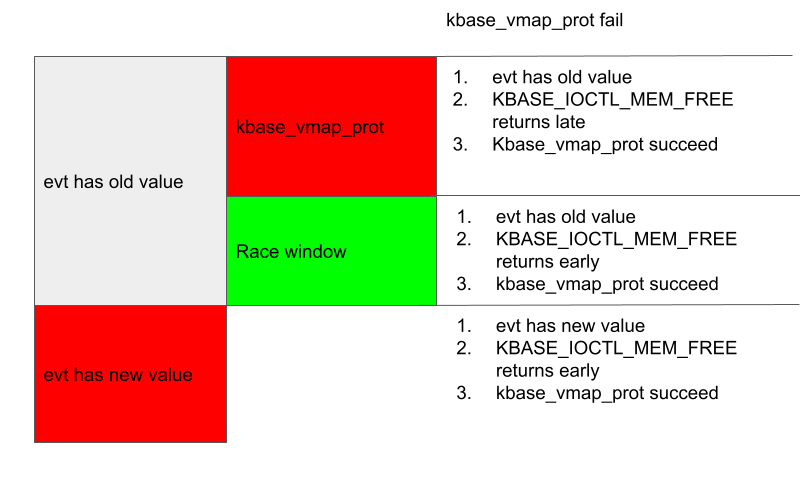

A common case of failure is when the interrupt happens during the function. In this case, the , which is a mutex, is held. To test whether the mutex is held when the interrupt happens, I can make an call that requires the during the interrupt from a different thread. There are many options, and I choose because this requires the most of the time and can be made to return early if an invalid argument is supplied. If the is held by (which calls ) while the interrupt happens, then cannot proceed and would return after the . Otherwise, the will return first. By comparing the time when these calls return, I can determine whether the interrupt happened inside the . Moreover, if the interrupt happens inside , then the address that I supplied to would not have been written to.kbase_vmap_protkctx->reg_lockioctlkctx->reg_lockKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_FREEkctx->reg_lockkctx->reg_lockKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEkbase_vmap_protKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_FREEKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_FREEioctlioctlkctx->reg_lockkbase_vmap_protevtkbasep_write_soft_event_status

So, if both of the following are true, then I know the interrupt must have happened before the race window ended, but not inside the function:kbase_vmap_prot

- If an started during the interrupt in another thread returns before the

KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_FREEKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATE - The address has not been written to

evt

The above conditions, however, can still be true if the interrupt happens before . In this case, if I remove the backing pages from the memory region, then the call would simply fail because the address , which belongs to the memory region, is no longer invalid. This then results in the returning an error.kbase_vmap_protKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_vmap_protevtKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATE

This gives me an indicator of when the interrupt happened and whether I should proceed with the exploit or try triggering the bug again. To decide whether the race is won, I can then do the following during the interrupt:

- Check if is written to, if it is, then the interrupt happened too late and the race was lost.

evt - If is not written to, then make a from another thread. If the returns and before the that is being interrupted, then proceed to the next step, otherwise, the interrupt happened inside and the race was lost. (interrupt happens too early).

evtKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_FREEioctlioctlKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEioctlkbase_vmap_prots - Proceed to remove the backing pages of the region that belongs to. If the returns an error, then the interrupt happened before the call and the race was lost. Otherwise, the race is likely won and I can proceed to the next stage in the exploit.

KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFevtKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEioctlkbase_vmap_prot

The following figure illustrates these conditions and their relations to the race window.

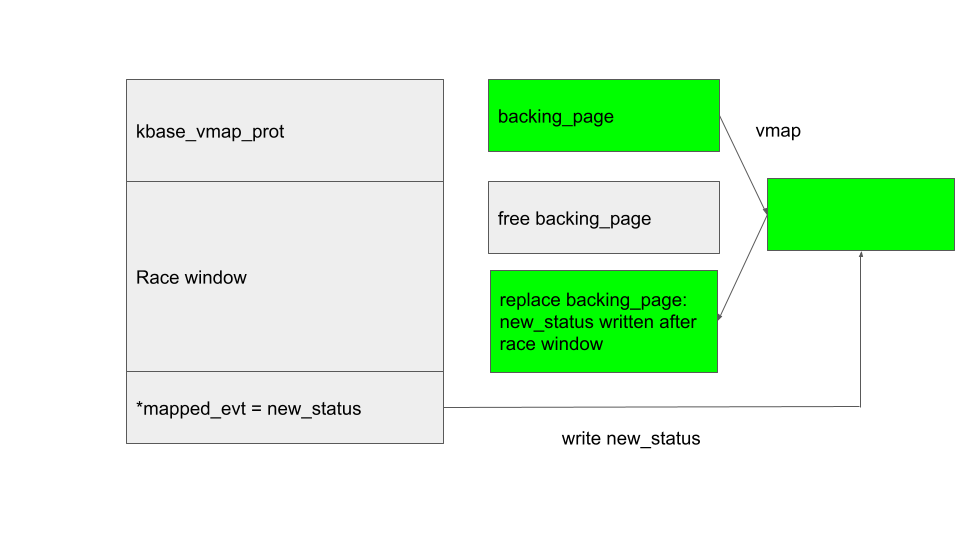

One byte to root them all

Once the race is won, I can proceed to free and then replace the backing pages of the region. Then, after the interrupt returns, will write to the free’d (and now replaced) backing page of the region via the kernel address created by .KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATEnew_statusKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFvmap

I’d like to replace those pages with memory pages used by the kernel. The problem here is that memory pages in the Linux kernel are allocated according to their zones and migrate type, and pages do not generally get allocated to a different zone or migrate type. In our case, the backing pages of the come from a user space application, which are generally allocated with the or the flag. On Android, which lacks the zone, this translates into an allocation in the with (for flag), or (for flag) migrate type. Memory pages used by the kernel, such as those used by the SLUB allocator for allocating kernel objects, on the other hand, are allocated in the with migration type. Many user space memory, such as those allocated via the syscall, are allocated with the flag, making them unsuitable for my purpose. In order to replace the backing pages with kernel memory pages, I therefore need to find a way to map pages to user space that are allocated with the flag.KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFGFP_HIGHUSERGFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLEZONE_HIGHMEMZONE_NORMALMIGRATE_UNMOVABLEGFP_HIGHUSERMIGRATE_MOVABLEGFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLEZONE_NORMALMIGRATE_UNMOVABLEmmapGFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLEGFP_HIGHUSER

The situation is similar to what I had with “The code that wasn’t there: Reading memory on an Android device by accident.” In the section “Leaking Kernel memory,” I used the asynchronous I/O file system to allocate user space memory with the flag. By first allocating user space memory with the asynchronous I/O file system and then importing that memory to the Mali driver to create a region with that memory as backing pages, I can create a memory region with backing pages in and the migrate type, which can be reused as kernel pages.GFP_HIGHUSERKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFZONE_NORMALMIGRATE_UNMOVABLE

One big problem with bugs in is that, in all uses of , there is very little control of the write value. In the case of the , it is only possible to write either zero or one to the chosen address:kbase_vmap_protkbase_vmap_protKBASE_IOCTL_SOFT_EVENT_UPDATE

static int kbasep_write_soft_event_status(

struct kbase_context *kctx, u64 evt, unsigned char new_status)

{

...

if ((new_status != BASE_JD_SOFT_EVENT_SET) &&

(new_status != BASE_JD_SOFT_EVENT_RESET))

return -EINVAL;

mapped_evt = kbase_vmap_prot(kctx, evt, sizeof(*mapped_evt),

KBASE_REG_CPU_WR, &map);

...

*mapped_evt = new_status;

kbase_vunmap(kctx, &map);

return 0;

}

In the above, , which is the value to be written to the address , is checked to ensure that it is either , or , which are one or zero, respectively.new_statusevtBASE_JD_SOFT_EVENT_SETBASE_JD_SOFT_EVENT_RESET

Even though the write primitive is rather restrictive, by replacing the backing page of my region with page table global directories (PGD) used by the kernel, or with pages used by the SLUB allocator, I still have a fairly strong primitive.KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUF

However, since the bug is rather difficult to trigger, ideally, I’d like to be able to replace the backing page reliably and finish the exploit by triggering the bug once only. This makes replacing the pages with kernel PGD or SLUB allocator backing pages less than ideal here, so let’s have a look at another option.

While most kernel objects are allocated via variants of the call, which uses the SLUB allocator to allocate the object, large objects are sometimes allocated using variants of the call. Unlike , allocates memory at the granularity of pages and it takes the page directly from the kernel page allocator. While is inefficient for small locations, for allocations of objects larger than the size of a page, is often considered a more optimal choice. It is also considered more secure as the allocated memory is used exclusively by the allocated object and a guard page is often inserted at the end of the memory. This means that any out-of-bounds access is likely to either hit unused memory or the guard page. In our case, however, replacing the backing page with a object is just what I need. To optimize allocation, the kernel page allocator maintains a per CPU cache which it uses to keep track of pages that are recently freed on each CPU. New allocations from the same CPU are simply given the most recently freed page on that CPU from the per CPU cache. So by freeing the backing pages of a region on a CPU, and then immediately allocating an object via , the newly allocated object will reuse the backing pages of the region. This allows me to write either zero or one to any offset in this object. A suitable object allocated by (a variant of that zeros out the allocated memory) is none but the itself. The object is created by , which can be triggered via many calls such as the :kmallocvmallockmallocvmallocvmallocvmallocvmallocKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFvmallocKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFvzallocvmallockbase_mem_phy_allockbase_alloc_createioctlKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALLOC

static inline struct kbase_mem_phy_alloc *kbase_alloc_create(

struct kbase_context *kctx, size_t nr_pages,

enum kbase_memory_type type, int group_id)

{

...

size_t alloc_size = sizeof(*alloc) + sizeof(*alloc->pages) * nr_pages;

...

/* Allocate based on the size to reduce internal fragmentation of vmem */

if (alloc_size > KBASE_MEM_PHY_ALLOC_LARGE_THRESHOLD)

alloc = vzalloc(alloc_size);

else

alloc = kzalloc(alloc_size, GFP_KERNEL);

...

}

When creating a object, the allocation size, depends on the size of the region to be created. If is larger than the , then is used for allocating the object. By making a call immediately after the call that frees the backing pages of a memory region, I can reliably replace the backing page with a kernel page that holds a object:kbase_mem_phy_allocalloc_sizealloc_sizeKBASE_MEM_PHY_ALLOC_LARGE_THRESHOLDvzallocKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALLOCioctlKBASE_IOCTL_STICKY_RESOURCE_UNMAPioctlKBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUFkbase_mem_phy_alloc

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_STICKY_RESOURCE_UNMAP, ...); //<------ frees backing page

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALLOC, ...); //<------ reclaim backing page as kbase_mem_phy_alloc

So, what should I rewrite in this object? There are many options, for example, rewriting the field can easily cause a refcounting problem and turn this into a UAF of a , which is easy to exploit. It is, however, much simpler to just set the field to zero:krefkbase_mem_phy_allocgpu_mappings

struct kbase_mem_phy_alloc {

struct kref kref;

atomic_t gpu_mappings;

atomic_t kernel_mappings;

size_t nents;

struct tagged_addr *pages;

...

}

The Mali driver allows memory regions to share the same backing pages via the call. A memory region created by can be aliased by passing it as a parameter in the call to :KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALIASioctlKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALLOCKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALIAS

union kbase_ioctl_mem_alloc alloc = ...;

...

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALLOC, &alloc);

void* region = mmap(NULL, ..., mali_fd, alloc.out.gpu_va);

union kbase_ioctl_mem_alias alias = ...;

...

struct base_mem_aliasing_info ai = ...;

ai.handle.basep.handle = (uint64_t)region;

...

alias.in.aliasing_info = (uint64_t)(&ai);

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALIAS, &alias);

void* alias_region = mmap(NULL, ..., mali_fd, alias.out.gpu_va);

In the above, a memory region is created using , and mapped to . This region is then passed to the call. After mapping the result to user space, both and share the same backing pages. As both regions now share the same backing pages, must be prevented from resizing via the , otherwise the backing pages may be freed while it is still mapped to the :KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALLOCregionKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALIASregionalias_regionregionKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_COMMITioctlalias_region

union kbase_ioctl_mem_alloc alloc = ...;

...

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALLOC, &alloc);

void* region = mmap(NULL, ..., mali_fd, alloc.out.gpu_va);

union kbase_ioctl_mem_alias alias = ...;

...

struct base_mem_aliasing_info ai = ...;

ai.handle.basep.handle = (uint64_t)region;

...

alias.in.aliasing_info = (uint64_t)(&ai);

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_ALIAS, &alias);

void* alias_region = mmap(NULL, ..., mali_fd, alias.out.gpu_va);

struct kbase_ioctl_mem_commit commit = ...;

commit.gpu_addr = (uint64_t)region;

ioctl(mali_fd, KBASE_IOCTL_MEM_COMMIT, &commit); //<---- ioctl fail as region cannot be resized

This is achieved using the field in the of a . The field keeps track of the number of memory regions that are sharing the same backing pages. When a region is aliased, is incremented:gpu_mappingsgpu_allockbase_va_regiongpu_mappingsgpu_mappings

u64 kbase_mem_alias(struct kbase_context *kctx, u64 *flags, u64 stride,

u64 nents, struct base_mem_aliasing_info *ai,

u64 *num_pages)

{

...

for (i = 0; i < nents; i++) {

if (ai[i].handle.basep.handle > PAGE_SHIFT) <gpu_alloc;

...

kbase_mem_phy_alloc_gpu_mapped(alloc); //gpu_mappings

}

...

}

...

}

The is checked in the call to ensure that the region is not mapped multiple times:gpu_mappingsKBASE_IOCTL_MEM_COMMIT

int kbase_mem_commit(struct kbase_context *kctx, u64 gpu_addr, u64 new_pages)

{

...

if (atomic_read(®->gpu_alloc->gpu_mappings) > 1)

goto out_unlock;

...

}

So, by overwriting of a memory region to zero, I can cause an aliased memory region to pass the above check and have its backing store resized. This then causes its backing pages to be removed without removing the alias mappings. In particular, after shrinking the backing store, the alias region can be used to access backing pages that are already freed.gpu_mappings

The situation is now very similar to what I had in “Corrupting memory without memory corruption” and I can apply the technique from the section, “Breaking out of the context,” to this bug.

To recap, I now have a whose backing pages are already freed and I’d like to reuse these freed backing pages so I can gain read and write access to arbitrary memory. To understand how this can be done, we need to know how backing pages to a are allocated.kbase_va_regionkbase_va_region

When allocating pages for the backing store of a , the function is used:kbase_va_regionkbase_mem_pool_alloc_pages

int kbase_mem_pool_alloc_pages(struct kbase_mem_pool *pool, size_t nr_4k_pages,

struct tagged_addr *pages, bool partial_allowed)

{

...

/* Get pages from this pool */

while (nr_from_pool--) {

p = kbase_mem_pool_remove_locked(pool); //next_pool) {

/* Allocate via next pool */

err = kbase_mem_pool_alloc_pages(pool->next_pool, //<----- 2.

nr_4k_pages - i, pages + i, partial_allowed);

...

} else {

/* Get any remaining pages from kernel */

while (i != nr_4k_pages) {

p = kbase_mem_alloc_page(pool); //<------- 3.

...

}

...

}

...

}

The input argument is a memory pool managed by the object associated with the driver file that is used to allocate the GPU memory. As the comments suggest, the allocation is actually done in tiers. First the pages will be allocated from the current using (1 in the above). If there is not enough capacity in the current to meet the request, then is used to allocate the pages (2 in the above). If even does not have the capacity, then is used to allocate pages directly from the kernel via the buddy allocator (the page allocator in the kernel).

When freeing a page, the same happens: first tries to return the pages to the of the current , if the memory pool is full, it’ll try to return the remaining pages to . If the next pool is also full, then the remaining pages are returned to the kernel by freeing them via the buddy allocator.

As noted in “Corrupting memory without memory corruption,” is a memory pool managed by the Mali driver and shared by all the . It is also used for allocating page table global directories (PGD) used by GPU contexts. In particular, this means that by carefully arranging the memory pools, it is possible to cause a freed backing page in a to be reused as a PGD of a GPU context. (The details of how to achieve this can be found in the section, “Breaking out of the context.”) As the bottom level PGD stores the physical addresses of the backing pages to GPU virtual memory addresses, being able to write to a PGD allows me to map arbitrary physical pages to the GPU memory, which I can then read from and write to by issuing GPU commands. This gives me access to arbitrary physical memory. As physical addresses for kernel code and static data are not randomized and depend only on the kernel image, I can use this primitive to overwrite arbitrary kernel code and gain arbitrary kernel code execution.

The exploit for Pixel 6 can be found here with some setup notes.kbase_mem_poolkbase_contextkbase_mem_poolkbase_mem_pool_remove_lockedkbase_mem_poolpool->next_poolpool->next_poolkbase_mem_alloc_pagekbase_mem_pool_free_pageskbase_mem_poolkbase_contextpool->next_poolpool->next_poolkbase_contextkbase_va_region

Conclusions

In this post I’ve shown how root cause analysis of CVE-2022-36449 revealed the unusual memory management in memory region, which then led to the discovery of another vulnerability. This shows how important it is to carry out root cause analysis of existing vulnerabilities and to use the knowledge to identify new variants of an issue. While CVE-2022-46395 seems very difficult to exploit due to a very tight race window and the limited write primitive that can be achieved by the bug, I’ve demonstrated how techniques from Racing against the clock—hitting a tiny kernel race window can be used to exploit seemingly impossible race conditions, and how UAF in memory pages can be exploited reliably even with a very limited write primitive.KBASE_MEM_TYPE_IMPORTED_USER_BUF

原文始发于Man Yue Mo:Rooting with root cause: finding a variant of a Project Zero bug

转载请注明:Rooting with root cause: finding a variant of a Project Zero bug | CTF导航